I have never been an autograph seeker. The whole notion of chasing after famous people and begging for scribbles has always seemed just another inane 20th century fad to me.

I have never been an autograph seeker. The whole notion of chasing after famous people and begging for scribbles has always seemed just another inane 20th century fad to me.

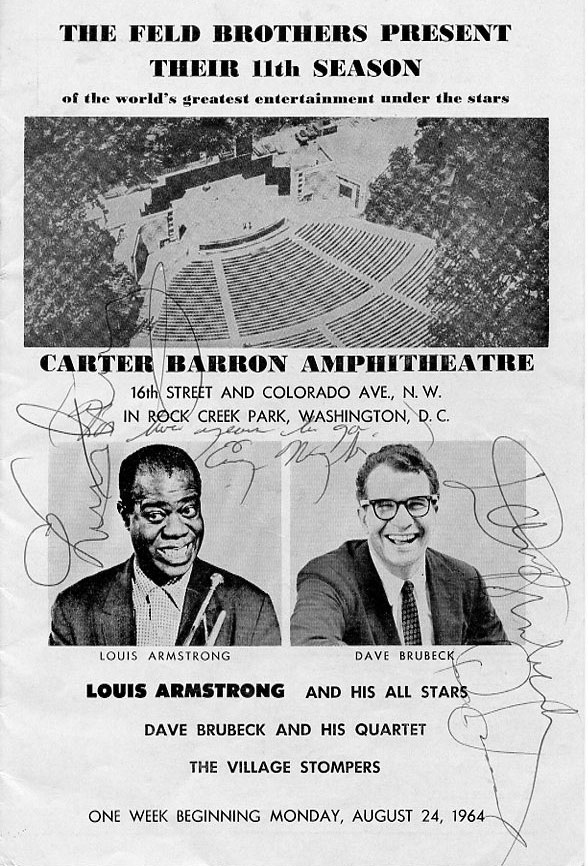

However, when I heard the news that Dave Brubeck had died at age 91, the first thing I thought of was the autographed program I still had in my desk from the 1964 concert series Brubeck played with his quartet at the Carter Barron Amphitheatre in Rock Creek Park.

He was the opening act for Louis Armstrong. That’s how cool the Carter Barron was back then.

I was a callow teen. I knew very little about jazz, but my brother Jeff was enthusiastic about all kinds of music, and he had an extra ticket. He invited me to come along. I remember the summer night was beautiful, the air soft and warm, the sky lit with stars. And the music blew my mind.

At that point in his career, Armstrong was so beloved by the American public that he had only to walk on the stage with his trumpet and his ubiquitous handkerchief to be enveloped in applause. And he was great, of course. But the songs he played were familiar to me, from having heard classic swing and popular dance music all during my childhood.

But when Brubeck and his quartet played, it was like nothing else. This was the same foursome who had recorded the groundbreaking album “Time Out” in 1959: Dave Brubeck on piano, Paul Desmond on alto sax, Gene Wright on bass and Joe Morello on drums. The brilliance of their playing seemed impossibly perfect and yet spontaneous.

Afterward, I would have been content to float home in a state of euphoria. But enough is rarely enough for my older brother, never a shy one. When Brubeck finished his set Jeff said, “Come on.”

I didn’t know what he was talking about, but a few minutes later we were standing at the edge of the stage, getting our programs autographed by the very gracious players. And before we left, Louis Armstrong cheerfully added his autograph to the collection.

The access we had that night seemed totally natural at the time. I doubt it could happen so easily in these security-conscious times. Crowds have gotten so big, concerts so grandiose and over-produced. The lights, cameras and fireworks create a barrier of technology to keep fans at distance. That night at the Carter Barron had the intimacy of a small club.

Today, in memory of Brubeck and his magical quartet I listened again to “Take Five,” their landmark hit. Even now, after hearing it hundreds of times, it gives me chills. It still has an almost miraculous sense of tension and possibility. Paul Desmond’s playing is sublime – sophistication and cool made audible. And Joe Morello was a revelation. He was the first drummer I ever heard who played the drums not simply to bang out the time, but as an instrument with a voice of its own, dancing with the bass line.

The year 1964 was full of dramatic change in the world. When you listen to Brubeck’s music, you can hear it coming.