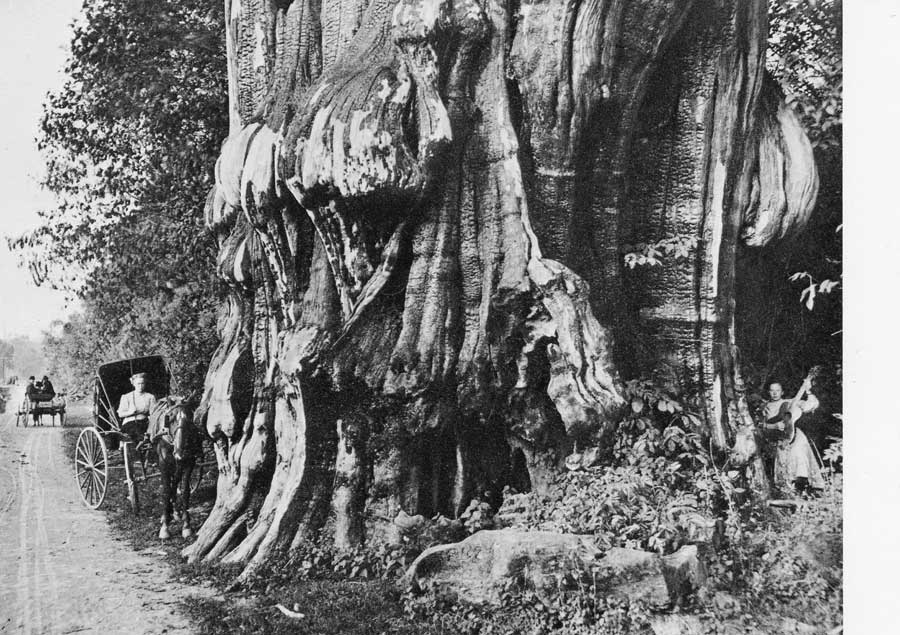

The slabs of stone curve impossibly high above the ground, looming like some silicate tidal wave about to crash.

We were hiking in Hanging Rock State Park in Danbury, North Carolina, where lime green buds swelling in the damp spring air lit the forest with a glow of energy. I had come to see a few of the state’s multitude of waterfalls. We visited three in the short time we had earmarked for outdoor exploration, and each one offered a different note in the music of water flowing over stones.

Yet though I was delighted by the waters, I was astounded by the stones. Hanging Rock State Park occupies some 7,000 acres in the Sauratown Mountains, sometimes described as “the mountains away from the mountains,” a range east of and apart from the nearby Blue Ridge Mountains. Ancient quartzite rocks worn down through millions of years frame every view with dramatic weight.

The beautiful oak and pine forest is interwoven with dark swathes of Canadian and Carolina hemlock. Groves of wild rhododendron, azalea, mountain laurel and galax flourish in the damp understory. We were there too early for the blooms, but the promise of spring was abundant and intoxicating in every direction while massive rocks chiseled by time into impossible sculptural forms and graced with the delicate tracing of lichens, moss, and ferns kept me spellbound.

I had been keen to see some of North Carolina’s waterfalls after reading about them in various online guides to the state. But my itinerary wasn’t limited to natural sights. There was also what some might call the baseball agenda.

In my growing passion for the game, I’ve begun to branch out, adopting a kind of when-in-Rome policy. Thus, when we learned that the local Class A minor league Greensboro Grasshoppers would be playing the Delmarva Shorebirds while we were in town, I was determined to see a game. It did not disappoint.

The Hoppers currently rank number 2 in the Sally League, but I had a feeling that no matter what happened on the scoreboard I would enjoy the experience because of Babe and Yogi.

Babe and Yogi are two frisky black labs who work as batdogs for the Grasshoppers. They retrieve the bats at home plate efficiently and cheerfully, and add charm to the easy-going minor league atmosphere.

Even though there was a light mist falling throughout the game, the fans lingered and cheered, especially when the game went to extra innings and Grasshoppers pulled out the win in the 11th inning with a walk-off hit.

And then there were fireworks. Not just fizzling little streaks of colored light either. Booming rockets of exploding color for five solid minutes. Totally awesome, even if it was minor league. It was an up close and personal experience, like getting close enough to waterfalls to feel the spray on your face, or climbing hundreds of steps carved in massive stone old as the planet.

Tomorrow is another Earth Day, and we celebrate once again the miracle of our lovely planet. Sometimes I think it’s funny that it’s called Earth, when that substance is such a small part of the whole. The precious earth which provides our food and the trees that keep our air breathable occupies only a thin layer above the dense stratum of solid and molten rock that make up most of the planet. Yet each year we pave and pollute more of it, as if we thought that more earth can be manufactured. Humans can be such short-sighted beings.

On Earth Day, and every day, I am grateful for the trees and the rocks, the dogs and the waterfalls, the fireworks of life.

And still hoping for an 11th inning miracle for us and our season on this planet.